WHAT HAPPENED TO THE FLOWER CARRIERS?

From Diego Rivera’s Paintings to the Fields of California

Text and Photographs by David Bacon

Dollars and Sense, January/February 2023

https://dollarsandsense.org/archives/2023/0123bacon.html

https://davidbaconrealitycheck.blogspot.com/2023/02/what-happened-to-flower-carriers.html

Along West Ocean Avenue in the summer of 2022, where Lompoc, California’s flower fields meet the edge of town, workers from Oaxaca and Guerrero were harvesting stock flowers. Even far from the rows where they labored, breezes carried the overpowering, almost sickly-sweet fragrance from thousands of blooms.

Stock flowers often anchor elaborate floral arrangements at funerals, their familiar smell calling up memories of churches and death. In Mexico, where Day of the Dead displays always feature brilliant orange marigolds, a family that has lost a child sometimes substitutes white stock blossoms on their altar. For them, the scent and color exercise a singular power to awaken memories of lost innocence.

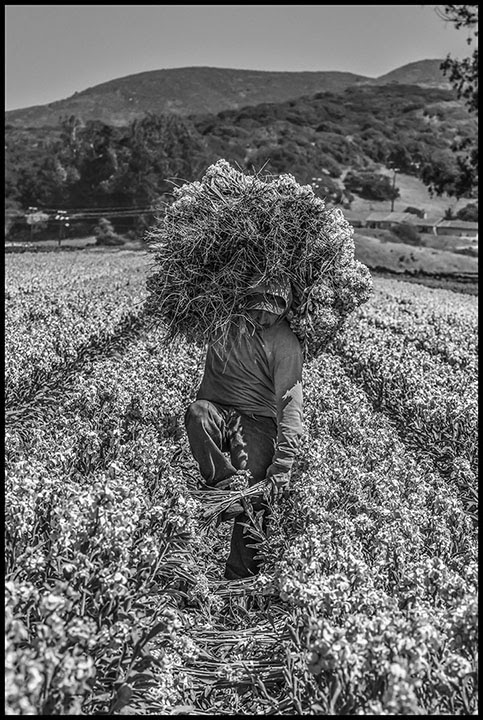

Workers in the Lompoc field were harvesting stock flowers in several colors-white for funerals, as well as deep purple, pale yellow, violet, and an orangey rose. As each worker moved down a row, he’d pull up a plant, roots and all. Gathering together half a dozen stalks, he’d reach for one of the paper-covered wire ties hanging from his belt. Wrapping the tie around the stems, he’d spin the bunch of flowers like a propeller, twisting it tight and banding them together.

Lompoc, Calif., 2022-Alberto Vasquez harvests stock flowers in the field, in a crew of Mexican farmworkers. All photographs are by (and (c)) David Bacon.

Lompoc, Calif., 2022-Daniel Moreno Hernandez twists a tie around a bunch of flowers he just picked.

Lompoc, Calif., 2022-A worker carries a bunch of stock flowers on his shoulder from the field after harvesting them.

In Mexico, things had not worked out as the revolutionaries of the 1910s and 1920s had hoped. The revolution’s changes slowed and eventually stalled, making life as an independent farmer in rural Mexico untenable, while the migrant labor of displaced Mexican campesinos became indispensable to the growth and profits of industrial agriculture in California. Eventually, Mexican farmers’ displacement and Californian landowners’ hunger for labor created the flower workers of Lompoc. The trajectory between Rivera’s paintings and the photographs in California’s fields traces visually the social transformation of the people who were once Rivera’s subjects, and then became migrants cutting flowers 2,000 miles away, a border and almost a century apart.

In Mexico’s countryside, by 1970 over 70% of small farmers could not live on the crops they were able to grow, or what they were able to earn by selling them, as Rivera’s flower sellers must do. From 1950 to 1976 Mexico’s population doubled, and the number of people living on each square kilometer of farmland did also, from 36 to 67. By then two-thirds of rural families couldn’t afford to eat meat most weeks. Mexico City’s growth couldn’t provide jobs for all those coming in from rural indigenous communities. Migration north to the maquiladora cities of the border, and across the border into U.S. fields, was increasingly the answer for survival.

According to the late Rufino Dominguez, one of the founders of the Frente Indigena de Organizaciones Binacionales, about 500,000 indigenous people from Oaxaca lived in the United States by 2000, 300,000 in California alone. Many came from communities whose economies are totally dependent on migration. The ability to send a son or daughter across the border to the north, to work and send back money, makes the difference between eating chicken or eating salt and tortillas. Migration means not having to cut furrows in dry soil for a corn crop that can’t be sold for what it costs to grow it. It means that dollars arrive in the mail when kids need shoes to go to school, or when a grandparent needs a doctor.

Mexico’s National Council of Population reported in the Census of 2000 that in Oaxaca 12.5% of people lived with no electricity, 26.9% lived in homes with no running water, and children got an average of 6.9 years of school. The displacement of people from Oaxacan communities tracks with the growth in poverty. By 2000, 18% of Oaxaca’s people had left for other parts of Mexico and the United States. As a result, according to the Indigenous Farmworker Study, one-third of the 700,000 farm workers in California come from Oaxaca and other states in southern Mexico. Of all farm workers in California, indigenous workers receive the lowest pay. According to the study’s author, Rick Mines, one-third reported earning the minimum wage, and an additional one-third reported earning less than the minimum-a wage that violates California state law. Most indigenous families live in crowded conditions in apartments or trailers. In some areas the most recent arrivals live outside in tents-even under trees.

Lompoc, Calif., 2022-A worker uses his foot to lever a bunch of flowers into his hand as he gathers the ones he has just picked.

TWO YEARS OF HEAT AND COVID IN THE SAN JOAQUIN VALLEY

Photographs by David Bacon

October 1, 2022 to February 10, 2023

Leo & Dottie Kolligian Library

University of California Merced

5200 N. Lake Road, Merced, CA 95343