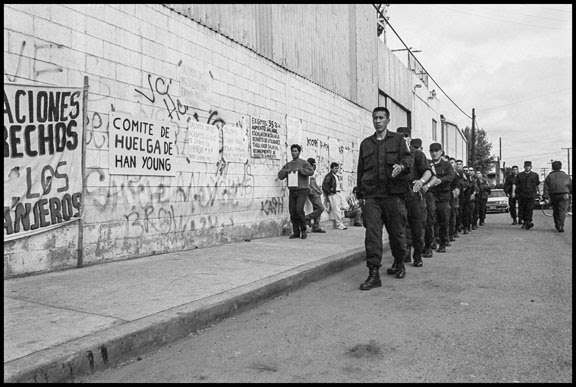

TIJUANA, BAJA CALIFORNIA NORTE – 1998 – Police arrive to escort strikebreakers into the struck Han Young maquiladora. The independent union there had the support of many unions in the U.S.

Since the North American Free Trade Agreement has been in effect, the economies of the United States and Mexico have become highly integrated. Working people on both sides of the Mexico/U.S. border are not only affected by this integration: they are its object. Corporate-controlled integration seeks to maximize profits and push wages and benefits to the bottom, manage the flow of people displaced as a result, roll back rights and social benefits achieved over decades, and weaken working-class movements in both countries.

U.S. and Mexican workers are part of a global system of production, distribution, and consumption. It’s not just a bilateral relationship. Jobs go from the United States and Canada to Mexico in order to cut labor costs. But from Mexico, those same jobs go China or Bangladesh or dozens of other countries where labor costs are even lower.

Multiple production locations undermine unions’ bargaining leverage. Grupo Mexico, a giant Mexican mining corporation, can use profits gained in mining operations in Peru to subsidize the costs of breaking a strike in Cananea and then buy the copper mines in Arizona and force U.S. workers out on strike as well.

The privatization of electricity in Mexico, which the Mexican Electrical Union (SME) has fought for two decades, does not just affect Mexicans. When Mexico’s laws restricting electricity generation to the government were weakened, a prelude to attacking the union directly, companies like San Diego Gas and Electric set up plants across the border. They produce power for the U.S. grid, at lower wages and with less regulation.

Energy maquiladoras, in effect, give utility unions in the United States a reason to help Mexican workers resist privatization. Cooperation, however, requires more than solidarity between unions facing the same employer. It requires solidarity in resisting neoliberal reforms like privatization and supporting the SME when it demands renationalization, as it does today.

It’s not just production. The United States also exports ideology. Education reform in Mexico comes from the Gates and Broad foundations. They are the same privatizers that attack U.S. teachers. In Mexico they’re supported by USAID, and their partner is Mexicanos Primero, which is run by Claudio X. Gonzalez and Claudio Gonzalez Guajardo, one of the wealthiest families in Mexico. Their attacks on teachers set the climate for the disappearance and murder of the 43 students in Ayotzinapa.

In both countries, the main union battles seek to preserve what workers have previously achieved, in a hostile political structure over which we have little control. Mexican unions are trapped in a state labor process, in which the government certifies unions’ existence, and to a large degree controls their bargaining. In the United States, labor is endangered by economic crisis, falling density, and a pro-corporate legal and political system. Trump and COVID certainly made this worse, but the crisis existed before they came along.

When Vicente Fox and the National Action Party defeated Mexico’s ruling party, the Party of the Institutionalized Revolution (PRI), in 2000, it created a new situation in which government-allied unions began to lose their privileged position. Employers and the government became more willing to use force and repression. Contingent employment became legal and widespread, as it has in the United States. Mexican unions today debate whether the situation of unions and workers has changed dramatically with the new administration of President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador, whom the left supported.

In the United States, labor law reform, national healthcare, and other basic pro-worker reforms have become almost politically impossible, even under Democratic presidents. The U.S. public sector, the most politically powerful section of the U.S. labor movement, has become the target of the U.S. right.

As the attacks against unions grow stronger, solidarity is becoming necessary for survival. Unions face a basic question on both sides of the border-can they win the battles they face today, especially political ones, without joining their efforts together?

Fortunately, this is not an abstract question, because important progress has taken place over the last two decades.

Continuar leyendo: https://davidbaconrealitycheck.blogspot.com/2020/10/building-culture-of-solidarity.html