A guest worker strings up wire supports for planting apple trees, in a Washington State field.

In Chicano and Mexican families, the grandfathers who came to the United States as braceros (and almost all braceros were men) are mostly gone now. These farmworkers were considered only temporary migrant laborers, yet despite being denied the right to settle in this country and raise families, thousands of them eventually did just that. Their perseverance created homes and communities throughout the Southwest. From the program’s inception in 1942 to its abolition in 1964, bracero labor produced enormous wealth for the growers who employed them.

That wealth had a price. Braceros were almost all young men, recruited into a program that held them in labor camps, often fenced behind barbed wire, separate from the population around them. When their contracts ended, they were summarily shipped back to Mexico. Growers used braceros to replace local farmworkers, themselves immigrants from Mexico and the Philippines, in order to keep wages low and often to break strikes. To bring their families here, braceros had to work many seasons for a grower who might finally help them get legal status. Others left the camps and lived without legal status for years.

In 1958, economist Henry Anderson charged in a report, (for which growers got the University of California to fire him) that, «Injustice is built into the present system, and no amount of patching and tinkering will make of it a just system … Foreign contract labor programs in general will, by their very nature, wreak harm upon the lives of the persons directly and indirectly involved, and upon the human rights our Constitution still holds to be self-evident and inalienable.»

Anderson’s call helped lead to the abolition of the bracero program, but his warning cannot be buried safely in the past. Today, contract labor in agriculture is mushrooming again, with workers brought mostly from Mexico, but also from Central America and the Caribbean. States are beginning to pass laws to deal with its impact, and a new bill in Congress does what Anderson cautioned against—expand the contract labor program for agricultural labor—in exchange for the promise of legal immigration status for some undocumented farmworkers.

Debate over today’s contract labor program unfolds in a virulently anti-immigrant atmosphere, much like that of the 1950s. Many supporters of proposals to benefit undocumented migrants believe that only major concessions can give such proposals a realistic chance of enactment. But the bracero program’s history, during a similar period of deportations and nativist hysteria, may provide an idea of what the future might look like if such compromises become law.

In the Cold War era of the 1950s and early 1960s, the U.S. government mounted huge immigration raids. Farm labor activists of that era charged they were intended to produce a shortage of workers in the fields. Fay Bennett, executive secretary of the National Sharecroppers Fund, reported that in 1954, “the domestic labor force had been driven out … In a four-month period, 300,000 Mexican illegals [sic] were arrested and deported, or frightened back across the border.”

All told, 1.1 million people were deported to Mexico that year, in the infamous “Operation Wetback.” The bracero program, begun in 1942, was already in place, organizing the recruitment of contract laborers in Mexico for U.S. farmers. As the raids drove undocumented workers back to Mexico, the government then relaxed federal requirements on housing, wages, and food for braceros.

Read more:

The American Prospect, November 25, 2019

https://prospect.org/labor/close-to-slavery-legalization-undocumented-farmworkers/

https://davidbaconrealitycheck.blogspot.com/2019/11/close-to-slavery-or-legalization.html

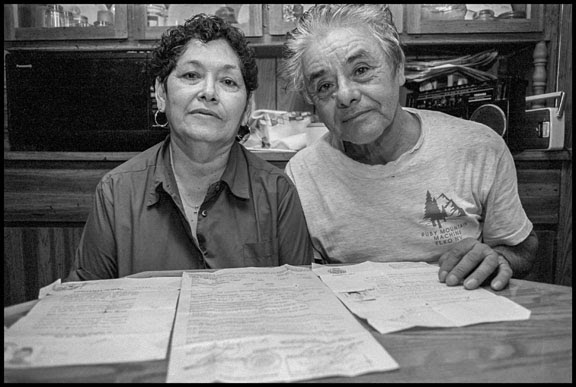

Amelia and Rigoberto Garcia, with the contracts he signed as a bracero on the table in front of them.

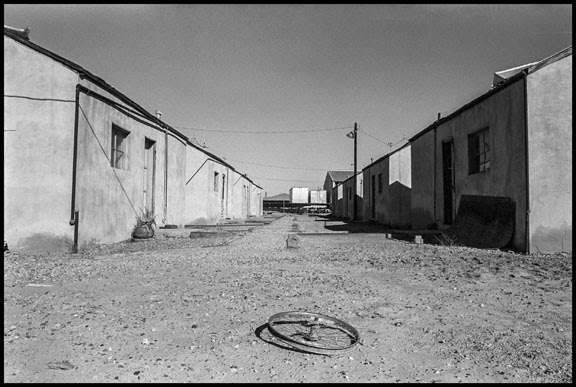

A camp in Blythe used for braceros in the 1940s and 50s, which still housed migrant farmworkers up until the 1980s.

Barracks in central Washington built to house contract workers brought to the U.S. by growers under the H2A visa program.